Click on the picture to see it up close

Dating Antique or Vintage Quilts. Quilts and quilt making are a reflection of the life and times of the women who made quilts. Although the technique of quilting existed throughout history (quilted items have been discovered in Egyptian tombs, for example, and French knights used quilted jackets under their armor), quilts as we think of them didn’t start showing up on the American scene until just prior to 1800.

I believe the earliest existing European quilts are a pair of whole cloth trapunto ones, telling the story of Tristan and Isolde dating from the early 1400’s. The oldest quilts in the Smithsonian collection go back to about 1780.

Early 1800

In colonial America, thread and needles were expensive. Cotton was not readily available – the cotton gin was not invented until 1793 – and so the majority of fabrics used in clothing were linens, wools and silks. What you might have seen prior to 1800 were quilted petticoats, worn for warmth. Quilts were almost always made of wool, unless they were remade from bed curtains or quilted petticoats.

However, the idea that all early quilts were made of worn clothing is a myth. Not to say that there weren’t any, but it is far more likely that a quilt would be made out of fabric bought specifically for that purpose, possibly to match bed curtains. It might also use the extra fabric left over after making clothes.

While it is true that many women were weaving their own fabrics in the early 1800’s, the tremendous time and energy needed to produce hand woven goods was generally not put into a luxury such as a quilt. A home weaver would be more likely to weave a blanket or coverlet. Generally, quilts were made by wealthier Americans on the Eastern Seaboard who had access to a tremendous variety of fabrics brought in by ship. Many early quilts still in existence today, therefore, are either made of imported fabric or have some imported fabric along with the American. Backings were often of linen, which was considered a utility fabric.

Early 1800’s quilts were usually large (120 X 120), and often whole cloth quilts, or quilts of whole panels, such as the Tree of Life. It might be a medallion or a stripy style quilt. Sometimes you would find quilts made of plain blocks (such as a simple Ohio star or nine patch) alternating with a plain block. Trapunto (stuffed work) quilts were made until the 1840’s when their popularity waned.

Glazed fabrics such as chintz (see photo, left), roller prints and pillar prints were popular. Fabrics were glazed with egg whites or honey. Some quilt edges were finished with a fringe, particularly on the East Coast. Quilting was done in straight lines, often with double and triple quilting, although flowers, baskets, feathers and wreathes were not uncommon.

Colors were glorious. The dye process was long and involved and colors changed depending on the mordents used. Home dyes used onionskin, nut shells and bark to create yellows, browns and greens, but they were not used as commonly as myth has it.

Mid 1800

Reliable permanent dyes were widely available in the mid 1800’s. However, green was considered fugitive – it often washed out or faded. In the early 1800’s, it was made by overdoing yellow with blue. Later in the century, the process was reversed, overdying blue with yellow. The applique quilts we now see with blue or tan leaves may have once been green. Another fugitive color, purple, could be made with lichens and seashells. Walnut hulls, hickory nut hulls, clay, or wood chips made brown. A deep brown with warm accents was made using manganese. Sumac, birch, oak, woodshed in general and iron made black.

Indigo blue and turkey red were very reliable dyes as they were made by the process for which the color was named. Indigo blue was a deep blue, although Prussian (Lafayette) blue and light blue was also available. Pinks and dark roses were also seen most likely made from a madder dyes. The picture on the left shows Turkey Red.

The mid 1800’s saw more appliqué quilts being made, with more elaborate quilting. Quilts were heavily quilted, often echo quilted or double quilted. Broderie Perse was an early 1800’s fad. In fact, you could purchase fabric specifically designed to be cut out and appliquéd. A later appliqué fad was were Baltimore Albums, red and green appliqué quilts and album samplers. They were as large as ever, although as the century progressed they tended to become slightly smaller and sometimes had two corners cut out for bedposts. Colors were bright and varied. You often saw deep yellow greens, Prussian blues, turkey reds, madders, double pinks (also called cinnamon pinks), fugitive purples, brilliant yellow/butterscotch, and aqua as well as graded or ombre prints.

The picture right shows an ombre print (also called a rainbow print) in the middle of the Ohio Star. The setting block is a fugitive double purple. You can see that a little bit better in the picture below.

The Civil War

The civil war and its aftermath brought a lot of changes to American women. Men took quilts with them to serve as bedding. If they were killed, they were often rolled in their bedding and buried. Quilts were also used to communicate the makers beliefs (like abolition), smuggle messages and supplies through enemy lines and raise money. The idea that quilt blocks were used to communicate Underground Railroad messages in the Virginia Basin has been disproven.

The quilts that did come home were often in terrible condition. Some of the finest quilts still extant from this period came from the families of soldier who retrieved them from encampments or purchased them from soldiers who were using them as if they were a common blanket. One quilt was retrieved from the back of a dead mule! Recognizing their beauty and value, some were looted from southern plantations.

It was after the civil war that the scrap quilt became popular. Due to the inevitable shortages of war, quilts really were made of discarded clothing at that time. Silk prices had come down around 1850 due to trading with the orient and many women had at least one good silk dress. But it was not useful for the hard work and shortages of everyday living most were forced to endure. The silk quilts popular during this period were probably made more out of sentiment and a need to keep busy while the men folk were away. The scraps of silk dresses and mens wear recalled happier times of balls and parties.

Sewing Machines

The sewing machine, which was really invented in the late 1700’s as a tool to make shoes, was redesigned and patented by Elias Howe, Jr., in 1846. Howe’s rival, Isaac Singer, received a patent in 1851 for an improved sewing machine, later adding a foot treadle for hands-free operation and a carrying case that doubled as a stand. Singer’s primary contribution to sewing machine history, however, was his marketing techniques. He was the Bill Gates of the 19th century.

The installment plan, and a trade-in allowance, was his clever marketing plan to put a sewing machine the home of every American woman, and it did work! By 1870, Singer was selling 200,000 sewing machines a year. Godey’s Lady’s Book praised the sewing machine as “the queen of inventions,” noting that “it will do all the drudgeries of sewing, thus leaving time for the perfecting of the beautiful in woman’s handiwork.” Quilts began to take advantage of straight line sewing and it was not uncommon to see hand-pieced quilt which was treadle quilted. A sewing machine was a status symbol, if a woman had one, she made sure to show it off.

Late 1800

Post civil war quilts took on more somber aspects. Women lost their husbands and sons in the war, Queen Victoria lost her husband Prince Albert and strict mourning protocol was followed. Mourning and half-mourning prints (Shaker Grays) similar to the one at left, of black & white, gray on gray, burgundy and deep purple were used with the madder browns (copper brown), dark chocolate, cocoa, double pinks and chrome orange’s (cheddar) of the period. Rich, deep, vivid colors became popular. This period marks the first of reliably colorfast synthetic dyes, making the fabrics of this period easier to wash as they wouldn’t have to be redyed.

Stripes and plaids were also used as well as textured fabrics, shirtings and lead-weighted silks. A lesser quality fabric and homespun (which may or may not have been spun at home) made an appearance, often on the backs of quilts. There was a veritable explosion of reasonably priced, colorfast cotton goods after the war as manufacturers which had geared up during the war sought reasons to keep up production.

The 1876 World exposition in Philadelphia had a pronounced influence on quilts. Many quilts, and embroidery designs began to show an oriental influence. “Impractical” silk, satin and velvet quilts were created using traditional styles, like the log cabin. The silks of that time period were often weighted with lead, to provide the rustle that the ladies loved so much. The more lead the better, since silk was sold by the pound. Unfortunately, it is this lead that causes the deterioration we see in silk quilts today. Chemical dyes also play a large factor in deterioration.

Early 1900

Wool quilts became more common, especially around the turn of the century. Quilts became more utilitarian – they were often tied rather than quilted. Applique was rare. If they were quilted, it was in large designs such as Baptist fans unless the quilt was being made as a “best” quilt. Mercerized thread, (a thread treated to improve strength) made its appearance in 1859 and began to be mass produced. The type and thickness of thread used to make a quilt is often a clue to its age.

As life improved, women found themselves with more time to spend on needle arts. Redwork became popular. Crazy quilts became a fad. These were quilts made of silk and satin and often carefully embellished with beads, embroidery, ribbons and hand painted blocks.

The early 20th century saw prints getting lighter and cheerier. Turkey red began to give way to a bluish red. Indigo dyed blues began to give way to simple blue vat dyes. We received Germanys’ aniline dye formulas as part of their war tribute for W.W.I. This meant the 30s and 40s quilts had better dyes, giving them more depth of color. Our greens and yellows improved and pastels became possible again. Purple finally became reliable, as did black.

Charming and happy prints as well as delicate solids appeared to contrast the depression. Kit quilts became popular, and it often seems like the majority of quilts made in that time period were Double Wedding Rings, Dresden Plates, Grandma’s Flower Gardens, Floral Appliqué and Sunbonnet Sue. Redwork Penny Square’s enjoyed continued popularity. Yo-yo’s were made by everyone and “Colonial Revival” quilts became popular, influenced by Marie Webster who wrote a book which may have inadvertently perpetuated quilting myths.

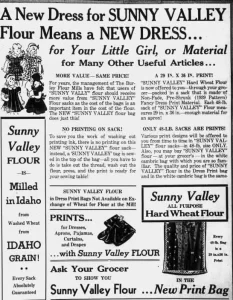

Feedsacks

The country entered into a new war and women once again found themselves forced to be resourceful. New quilts were made out of old tops. As a marketing ploy, grain producers began to package feed in print sacks. Men were sent to the store with instructions to buy feedsacks in specific colors and quantities. Three were needed to make a woman size dress. Novelty feedsacks to make aprons or dolls were available.

Sometimes called feedbags, textile bags and “chicken linen,” these terms refer to the bags that were purchased with products like flour, grain, feed or seed in them. They were also used for flour, salt, sugar and other baking necessities. Generally made of cotton or burlap, they might be tightly woven or loosely woven depending on what they carried. When the product inside was used up the cloth bag was recycled (long before that word was fashionable) into garments, quilts and household articles.

When the war ended, the interest in handmade items waned. Women were joining the work force in unprecedented numbers and had no time to make bedding. Especially when they could now afford to buy it! It was associated with poorer times. Interest in quilting was revived in the late 1970’s, with the advent of the Bicentennial and the renewed interest in our life of our forebears.

Share Your Story

Do you have a story or a picture to share? Please send it to krisdriessen@gmail.com. Thanks!